Medical hypnosis: a multi-faceted tool

Although there is, to date, no consensus on the descriptions of hypnosis, many researchers and theorists agree on the American Psychological Association (APA) definition that defines hypnosis as “a state of attention involving focused attention as well as a reduction in peripheral awareness, characterized by an increased ability to respond to suggestion” [1]. It includes three main components:

- Absorption: Ability to get fully involved in mental or imaginary imagery. Example: The practitioner guides you in visualizing an imaginary landscape. You see vivid details, feel the fresh air on your skin, and hear the birds singing. You are so engrossed in this imaginary scene that you temporarily forget your real environment.

- Dissociation: Functional separation between psychic or mental elements that are usually combined. Example: The practitioner helps you focus your attention on a feeling of lightness in one part of your body. During this time, you feel as though pain in another part of your body is disconnected from you. This dissociation allows you to manage pain more effectively by reducing the perception of pain.

- Suggestibility: Increased tendency to comply with practitioner instructions. Example: The practitioner suggests that you experience a feeling of warmth and comfort in the painful area of your body. You follow this suggestion and actually feel that soothing warmth, which helps to reduce the pain.

Over the years, hypnosis has been refined to become a valuable therapeutic tool. Today, medical hypnosis helps treat many disorders, from stress to anxiety to chronic pain, by guiding the subject to their own resources and solutions.

More specifically, this article explores medical hypnosis from various perspectives. After precisely defining this practice, we will dive into the brain mechanisms that underlie its therapeutic effects. Finally, we will review the main clinical applications of medical hypnosis.

Medical Hypnosis vs Hypnotherapy

Before getting to the heart of the matter, it is important to understand the difference between the terms “medical hypnosis” and “hypnotherapy.” Indeed, although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they are two distinct practices.

Hypnotherapy is, in general, practiced in private practices by trained and certified doctors or psychologists and aims at personal development, well-being or psychological support (such as stopping smoking). It encompasses various approaches and techniques (analytical, dreamlike, cognitive-behavioral, etc.), which do not always have formal scientific validation.

Medical hypnosis, on the other hand, is practiced in hospitals, in private clinics or medical offices and aims to treat specific medical problems. It is carried out by health professionals (psychologist, nurses, anesthesiologist), who have completed additional training in medical hypnosis in addition to their basic training. It is subject to the strict regulations of the medical profession and is based on validated and standardized medical protocols as well as scientific research. Medical hypnosis can be partially or fully reimbursed by health insurance, depending on the health condition being treated and individual insurance policies.

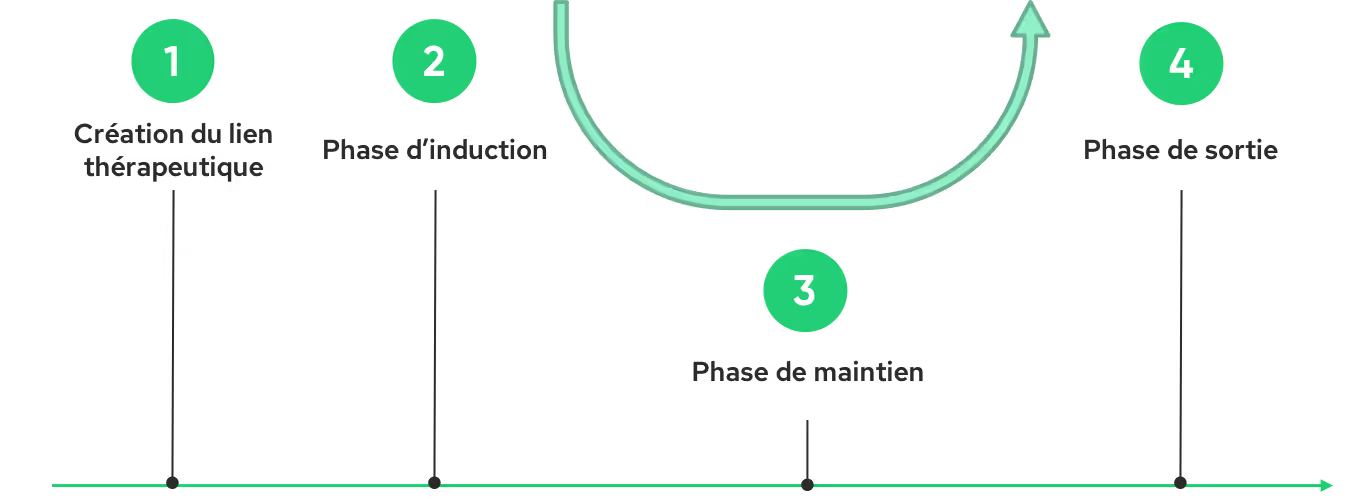

Medical hypnosis is inspired by formal hypnosis (a traditional practice based on direct suggestions) and conversational hypnosis (the hypnotic state is induced indirectly during an apparent “conversation”) [2]. La Figure 1 below shows the course of a session:

La creation of the therapeutic link established between the practitioner and the patient is the first essential step in a successful hypnosis session. This relationship, based on empathy and clear communication, creates a climate conducive to relaxation and openness to suggestions. The induction phase, which follows, aims to guide the patient to a hypnotic state, conducive to receiving suggestions. The practitioner then uses various techniques: verbal suggestions, guided visualizations and breathing exercises. Once this state is reached, the maintenance phase allows to deepen the hypnotic state and to introduce specific therapeutic suggestions. For example, in the case of pain management, the practitioner may invite the patient to visualize their pain as an entity that breaks away from their body and then gradually subsides. These suggestions, reinforced by metaphors and analogies, aim to change the perception of pain and promote a state of well-being. Finally, the output phase allows the patient to gradually return to a normal state of consciousness, while inviting him to integrate the benefits of the session. The practitioner may suggest that the patient maintain the feelings of calm and well-being experienced during the session, and mobilize them if necessary.

What happens in the brain?

Thanks to advances in neuroimaging, we are beginning to identify brain areas linked to the hypnotic state. Medical hypnosis makes it possible to modulate brain activity in regions involved in self-awareness, mental imagery, emotional regulation, attention and pain perception (for a more in-depth review, consult [3]).

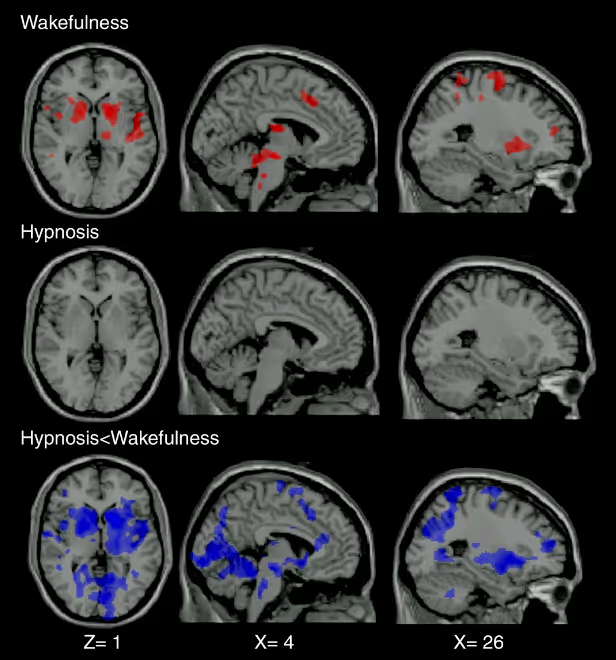

The authors of a 2009 study explored the differences in brain activation induced by painful and non-painful stimulations in healthy subjects under hypnosis and in a normal state of wakefulness [4]. While pain stimulations in a state of wakefulness predictably activated the regions involved in pain perception, these same stimulations, under hypnosis, did not cause significant activation of these regions (Figure 2). The last line in Figure 2 is a comparison of activation patterns between the normal arousal state and the hypnotic state. Regions activated during painful stimulation (in blue in the figure) are significantly less active under hypnosis only in a normal state of wakefulness. These results suggest that hypnosis could significantly modulate the brain processes involved in pain perception.

Beyond the activity of these regions, hypnosis also changes the way in which these different regions communicate with each other [5]. Some connections are strengthened, while others are weakened. These changes in the functional connectivity could explain the varied effects of hypnosis, such as reducing pain, improving concentration, or changing sensory perceptions. In addition, hypnosis could also promote release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins, which play a role in regulating mood, pain, and relaxation [6].

It is essential to note that these results are the result of ongoing research and that our understanding of hypnosis is constantly evolving.

Medical applications

Hypnosis can be used in a variety of clinical settings to combat anxiety, pain, and sleep disorders. It thus contributes to significantly improving the well-being and quality of life of patients of all ages, from children to the elderly. The methods used are adapted to each age group. Published in 2015 by the Sparadra association, the”Practical manual of hypnoanalgesia for pediatric care“by Bénédicte Lombart and her collaborators offer a range of concrete tools to implement hypnoanalgesia (pain management) in children. In particular, this guide offers scripts adapted to each age, using simple language and familiar metaphors to support young patients. More recently, in 2024, Geneviève Perennou and Serge Sirvain coordinated the production of a cheat sheet specifically designed for the elderly. This tool lists the hypnotic techniques best suited to this audience, thus offering professionals a valuable resource to support these people.

Currently, the use of medical hypnosis for pain management is the application that has the highest level of scientific proof. Indeed, hypnosis makes it possible to reduce the perception of acute pain (burn care, injection, dental care, etc.) [7], chronic [8] and post-surgical [9] in many clinical contexts. It can also help pregnant women manage pain and anxiety during pregnancy and birth. [10]

In addition to anesthesia or sedation (hypnosedation), medical hypnosis can decrease anxiety, pain, and medication consumption in the operating room, while accelerating post-operative recovery [11]. The effectiveness of hypnosis varies according to individual suggestibility [12]. A study, carried out with 3,632 patients, showed that hypnosis reduced pain by 42% in highly suggestible subjects and 29% in those moderately suggestible [13]. Even the less suggestible ones benefit, although in a more limited way.

The use of hypnosedation in addition to general or local anesthesia is recommended by the SFAR (French Society of Anesthesia and Resuscitation).

🎥 If you want to know more about the use of medical hypnosis in hospitals, we recommend watching the Belgian documentary “My voice will accompany you” released in 2020 on Netflix. This film explores how two Belgian anesthesiologists, Fabienne Roelants and Christine Watremez, use hypnosis in the operating rooms of Clinics Saint-Luc in Brussels.

With regard to the anxiety management, studies show that hypnosis can significantly reduce preoperative anxiety, thus improving the overall patient experience for both adults and children [9]. Patients undergoing invasive or painful medical procedures, such as endoscopies [14], biopsies [15], and colonoscopies [16], may also benefit from hypnosis to reduce anxiety. A meta-analysis was carried out in 2019 in order to assess the effectiveness of hypnosis in the treatment of anxiety [17]. The analysis of the 17 trials included in this study indicates that, on average, people who underwent hypnosis therapy performed better than 79% of people in the control group. In this study, hypnosis is more effective in reducing anxiety when combined with other psychological interventions (cognitive-behavioral therapies, biofeedback, etc.) than when used alone [17].

Hypnosis is particularly indicated in the management of disorders with a psychosomatic component, such as gastrointestinal disorders. Indeed, some patients with irritable bowel syndrome may be refractory to conventional therapies. A meta-analysis showed that hypnosis was a safe method that relieved long-term symptoms for 54% of patients [18]. In addition, it has a proven track record in managing symptoms associated with diseases such as cancer (especially in palliative care; [19]) and fibromyalgia [20]. By reducing anxiety, pain and improving sleep, hypnosis contributes significantly to the well-being of patients with these pathologies. It is also used to alleviate the side effects of cancer treatments, including nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy and radiation therapy [21].

The benefits of hypnosis in medicine are undeniable. By combining this technique with other tools, such as vr, we can look at new perspectives to improve the management of pain and anxiety. Immersive environments created by virtual reality could enhance the effectiveness of hypnotic suggestions, offering patients a more fun and complete therapeutic experience. To find out more about our offers, visit this page.

The take-home message

- Hypnosis is a altered state of consciousness, characterized by a focused attention and increased suggestibility.

- Medical hypnosis differs from hypnotherapy in that medical framework And its standardized protocols.

- Hypnosis offers a non-drug approach To manage the soreness And theanxiety and Relieve symptoms linked to chronic diseases or cancers.

To go further

SFAR opinion on hypnosedation:

The different currents of hypnosis:

- https://www.hypnose.fr/hypnose/courants-hypnose-therapeutique/,

- https://books.google.fr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=en34AgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=diff%C3%A9rents+types+d%27hypnose+m%C3%A9dicale&ots=Jzu4MHU-YJ&sig=flCz-A67neA0wJlduMMNtbuQFiI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=diff%C3%A9rents%20types%20d'hypnose%20m%C3%A9dicale&f=false

Netflix documentary:

Cover photo credit: My voice will accompany you

References

[1] G.R. Elkins, A.F. Barabasz, J.R. Barabasz, J.R. Council, and D. Spiegel, “Advancing Research and Practice: The Revised APA Division 30 Definition of Hypnosis ”, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypno., vol. 63, nO 1, p. 1-9, Jan. 2015, doi: 10.1080/00207144.2014.961870.

[2] A. Bioy, “Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy”, EMC - Psychiatrist., vol. 1, nO 1, p. 1-13, Jan. 2004, doi: 10.1016/S0246-1072 (02) 00083-4.

[3] G. De Benedittis, “Neural mechanisms of hypnosis and meditation”, J. Physiol. -Paris, vol. 109, n.O 4‑6, p. 152‑164, Dec. 2015, dec. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2015.11.001.

[4] A. Vanhaudenhuyse et al., “Pain and non-pain processing during hypnosis: A thulium-YAG event-related fMRI study”, NeuroImage, vol. 47, nO 3, p. 1047—1054, Sept. 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.031.

[5] V. De Pascalis, “Brain Functional Correlates of Resting Hypnosis and Hypnotizability: A Review,” Brain Sci., vol. 14, n.O 2, p. 115, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.3390/brainsci14020115.

[6] D.J. Acunzo, D.A. Oakley, and D.B. Oakley, and D.B. Terhune, “The neurochemistry of hypnotic suggestion,” Am. J. Clin. Hypno., vol. 63, nO 4, p. 355‑371, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.1080/00029157.2020.1865869.

[7] C. Kendrick et al., “Hypnosis for Acute Procedural Pain: A Critical Review ”, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypno., vol. 64, nO 1, pp. 75—115, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1080/00207144.2015.1099405.

[8] P. Langlois et al., “Hypnosis to manage musculoskeletal and neuropathic chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis”, Neuroscia. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 135, p. 104591, apr. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104591.

[9] J. Zeng, L. Wang, Q. Cai, Q. Cai, J. Wu, and C. Zhou, “Effect of hypnosis before general anesthesia on postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing minor surgery for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Gland Surg., vol. 11, n.O 3, p. 588‑598, March 2022, doi: 10.21037/gs-22-114.

[10] K. Madden, P. Middleton, A. M. Cyna, A. M. Cyna, M., M., M., M., M., Matthewson, and L. Jones, “Hypnosis for Pain Management During Labour and Childbirth,” Cochrane Database System Rev., vol. 2016, nO 5, May 2016, doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd009356.pub3.

[11] M. Holler, S. Koranyi, B. Strauss, and J. Strauss, and J. Rosendahl, “Efficacy of Hypnosis in Adults Undergoing Surgical Procedures: A meta-analytic update”, Wink. Psychol. Rev., vol. 85, p. 102001, April 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102001.

[12] I. Kirsch and S. J. Lynn, “The Altered State of Hypnosis: Changes in the Theoretical Landscape.” Am. Psychol., vol. 50, n.O 10, p. 846‑858, Oct. 1995, doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.50.10.846.

[13] T. Thompson et al., “The effectiveness of hypnosis for pain relief: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 85 controlled experimental trials”, Neuroscia. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 99, p. 298‑310, April 2019, April 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.02.013.

[14] F. Bobin, C. Garreau, and J.R. Lechien, and J.R. Lechien, “Safety and Feasibility of Hypnosis-Induced Sleep Endoscopy in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients.”, Ear. Nose. Throat J., p. 014556132311700, Apr. 2023, April 2023, doi: 10.1177/01455613231170094.

[15] F. Hızlı et al., “The effects of hypnotherapy during transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate needle biopsy for pain and anxiety,” Int. Urol. Nephrol., vol. 47, nO 11, p. 1773‑1777, nov. 2015, nov. 2015, doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1111-0.

[16] G. Elkins, J. White, P. Patel, P. Patel, J. Marcus, J. Marcus, J. Marcus, M., M., Perfect, and G. H. Montgomery, “Hypnosis to Manage Anxiety and Pain Associated with Colonoscopy with Colonoscopy for Colorectal Cancer Screening: Case Studies and Possible Benefits ”, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypno., vol. 54, n.O 4, p. 416-431, dec. 2006, doi: 10.1080/00207140600856780.

[17] K.E. Valentine, L.S. Milling, L.J. Milling, L.J. Clark, and C.L. Moriarty, “The Efficacy of Hypnosis as a Treatment for Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis ”, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypno., vol. 67, nO 3, p. 336‑363, July 2019, doi: 10.1080/00207144.2019.1613863.

[18] R. Schaefert, P. Klose, G. Moser, and W. Moser, and W. Häuser, “Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety of Hypnosis in Adult Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Psychosom. Med., vol. 76, n.O 5, p. 389-398, June 2014, doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000039.

[19] J. Bissonnette, E. Dumont, A.-M. Pinard, M. Landry, P. Rainville, and D. Ogez, and D. Ogez, “Hypnosis and music interventions for anxiety, pain, sleep and well-being in palliative care: systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ Support Palliate. Care, vol. 13, nO e3, p. e503‑e514, Dec. 2023, dec. 2023, doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003551.

[20] G. Elkins, “Efficacy of Hypnosis Interventions: Fibromyalgia, Sleep, Oncology, Test Anxiety, and Beliefs,” Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypno., vol. 71, nO 4, p. 273‑275, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1080/00207144.2023.2243785.

[21] J. Richardson, J. E. Smith, G. Mccall, G. Mccall, A. Mccall,, A., A. Richardson, K., Pilkington, and I. Kirsch, “Hypnosis for nausea and vomiting in cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review of the research evidence,” Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.), vol. 16, nO 5, p. 402‑412, Sept. 2007, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00736.x.

Want to test Lumeen for 30 days with no commitment?